This case study details on the emergence and rise of Freeport's mining operations in Indonesia. For almost 30 years, it has built on its mining concession and increased its output to almost 200,000 cubic feet/day of ore. It has sought to settle environmental issues and the protection of the stakes of indigenous people. Yet, critics were not convinced of the company's actions.

V. Kasturi Rangan; Arthur McCaffrey

Harvard Business Review (504061-PDF-ENG)

February 23, 2004

Case questions answered:

- Identify the stakeholder groups and conduct a Stakeholder Assessment. What should be done fairly quickly to manage stakeholders?

- What are you going to do with all the stakeholders?

Not the questions you were looking for? Submit your own questions & get answers.

Freeport Mine, Irian Jaya, Indonesia: "Tailings & Failings" - Stakeholder Analysis Case Answers

BRIEFING NOTE

TO: Richard C. Adkerson, CEO of Freeport Mine-McMoRan Copper & Gold Inc.

SUBJECT: Change Strategy from “Wage a Fight” to “Work It Out” with Nonmarket Stakeholders

Situation at Freeport Mine:

Looking through the past 30 years of Freeport’s mining operations in Indonesia, it is clear that the company’s strategy to “Wage a Fight” with nonmarket stakeholders worked. Freeport Mine involved the government in providing security for its operations, paying millions to the army and police.

It defended itself vigorously in court. All the while, it was digging more and more copper, gold, and silver. It is now one of the largest copper, gold, and silver mines in the world.

While fighting with nonmarket stakeholders and surviving under the new government, Freeport Mine managed to more than double its mining output over a ten-year period, reaching $1.9B in revenues by 2002.

However, the amount of criticism from nonmarket stakeholders has been intensifying. Local environmental activists are charging that Freeport harmed glaciers, degraded rainforests, and clogged rivers with mine tailings, killing fish and other fauna.

They have been successful in pressuring organizations such as Overseas Private Investment Corporation and the World Bank to cancel their insurance policies for the mine.

Indigenous groups who have been suppressed for all these years are staging violent protests and filing lawsuits over human rights and environmental abuses. This is gathering international attention and increasing pressure on shareholders to force Freeport Mine to make operational changes.

Strategies that Freeport Mine Has to Consider

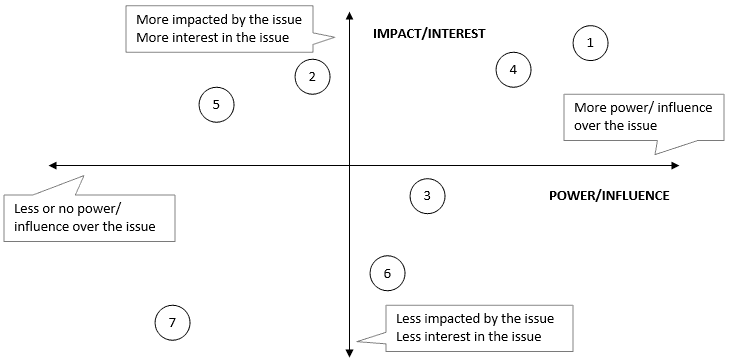

There are several stakeholders Freeport has to deal with (see Stakeholder Assessment, Appendix). Some of them have more power and influence. Some are more interested in what Freeport does (see Stakeholder Influence/Interest Grid, Appendix).

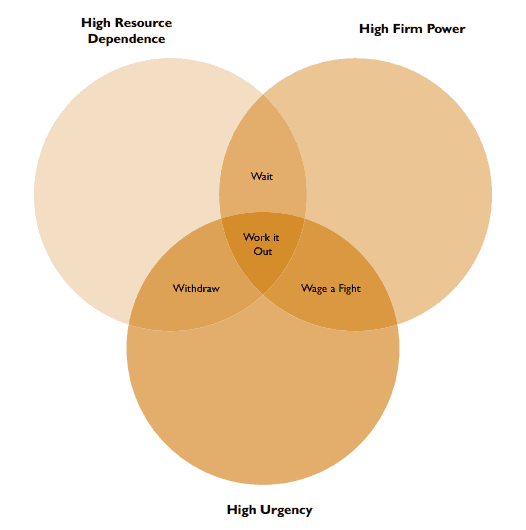

There are four main strategies that Freeport Mine can consider to manage its disputes with nonmarket stakeholders:

- Wage a Fight. Continue responding to stakeholders in an adversarial manner. Use tactics such as organizing potential allies, filing lawsuits or requesting injunctions, mobilizing public opinion, seeking the support of political elites or scientific experts, physically intimidating stakeholders, or relying on the police authority of the state. This strategy worked in the past because its dependence on its critics was low. Although vocal, the activist stakeholders were unable to affect sales of the company’s copper, gold, and silver, which were sold mainly to other businesses rather than individuals. Freeport Mine was not particularly concerned about its reputation. It was able to defeat activist shareholders in proxy voting. Freeport held considerable coercive power through its relationship with the military government in Indonesia and utilitarian power through its ability to offer jobs, tax revenue, and other benefits to the local community. Nonetheless, it considered it urgent to deal with its adversaries, mainly because of the threat to its risk insurance. However, moving forward, issues raised by many of these nonmarket stakeholders will cause problems with production (labor strikes) and sale of extracted ore (boycotts due to pressure from customer shareholders) and significantly increase the company’s liabilities (lawsuits) which market stakeholders (shareholders, investors) don’t want to see. Hence, this strategy is not appropriate moving forward.

- Wait. Wait for the management to bide its time and wait. Waiting is not about ignoring stakeholder demands. It is a strategy to use the passage of time to the company’s advantage. However, in this case, it would not be an appropriate strategy. Matters will simply become more urgent, and nonmarket stakeholders will gather more support.

- Withdraw. Change direction to remove itself from stakeholder conflict. Move to a different place where there is less opposition, or give up and accept defeat. This strategy is not feasible for Freeport Mine, given how much the company invested in setting up Indonesia’s operations. Market stakeholders (shareholders and investors) will not approve of this.

- Work It Out. Management should actively engage with stakeholders in an ongoing dialogue to arrive at mutually acceptable solutions. Working it out means finding new options and seeking common ground. Engaging nonmarket stakeholders will lower risks for Freeport operations and lower spend required to fight these stakeholders.

RECOMMENDATION:

Freeport Mine needs to change its strategy to “Work It Out,” with its nonmarket stakeholders adopting more responsible practices in their mining operations.

My recommendation is to establish committees responsible for social and community affairs, human rights, and environmental compliance. They will work with local government, indigenous population, environmental NGOs, and other nonmarket stakeholders to come up with innovative agreements that are appropriate for all parties involved.

Investments in communities (public health assistance, community social funds, STEM education programs) will help residents see the benefits of having Freeport continue to operate. Freeport would also need to change its processes and procedures related to environmental management.

By involving and collaborating with environmental organizations, it can identify areas of improvement and work with these organizations to prevent, mitigate, or ameliorate adverse environmental impacts.

Finally, Freeport Mine needs to become more transparent. It should set up independently verified reporting arrangements with its stakeholders.

Involving and collaborating with nonmarket stakeholders will lower the risk of them prevailing on government regulators to change their policies, bring a lawsuit based on human rights or environmental law to block a project, or use media to damage the company’s reputation.

A positive relationship with these stakeholders will also influence Freeport Mine customers’ decision to buy their products and shareholders to invest in the company and not put any roadblock on revenue-generating projects.

To manage this change, management would need to leverage different communication strategies with various stakeholders (see Communication Strategy, Appendix). Shareholders and the government would need to be managed closely (work as a team with them).

The concerned local population and environmental groups would need to be consulted with and kept satisfied (open dialogue, inclusion in a specific decision).

Employees, the army, and the police would need to be informed (direct, specific communication). Other groups who are mere bystanders would need to be monitored.

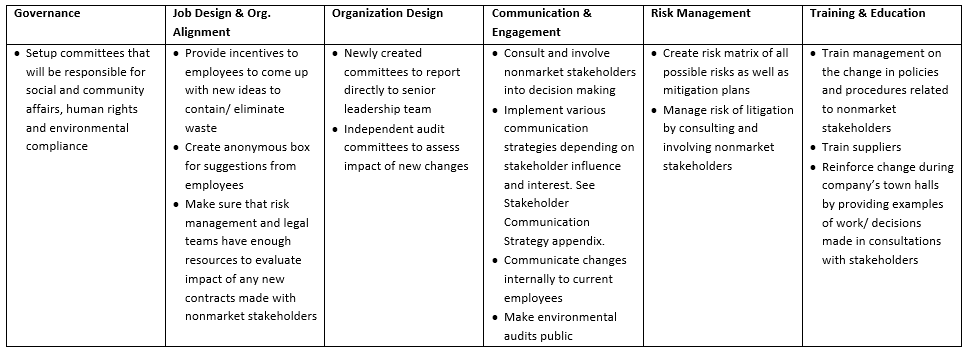

Change Planning Tool (see Appendix), which is meant to provide detailed plans, should be used by management as this is a significant change in the strategy. It will help Freeport Mine to stay on track and manage this change.

APPENDIX

STAKEHOLDER ASSESSMENT

| Stakeholder | Change Impact | Concerns/WIIFMs | Importance to Project | Commitment Level |

| #1 Shareholders | With increased production, they are rewarded financially | Concerned with the amount of liabilities, remediation costs, and lawsuits | Very important. They provide the capital necessary to expand operations | Very committed. Want to see increased production to improve return on their investments |

| #2 Current employees | They are suffering from human rights violations. | Need money as other job opportunities are scarce. However, don’t want to be oppressed/ taken advantage of. | Important. Many works at the mine. If they are not happy, the company has to deal with riots, fires, injuries, and killings. | Somewhat committed to expanding production as more jobs will be available. However, want higher wages or fewer hours for the same wages. Want better treatment. |

| #3 Local indigenous Komoros and Amunge people not working in the mine | Project expansion has an impact on the island’s Alpine glaciers and water pollution, and effects on culture. | Their living depends on the environment. Fishes are dying due to pollution caused by mining. | Not very important. However, their concerns have been reaching government officials. Also, current employees live in the same community and share similar concerns. | Not committed to expanding production. They do, however, want communal benefits such as new homes, schools, places of worship, and infrastructure. |

| #4 Indonesia government | Receive more taxes with increased production. | Need money to maintain order and peace in the country | Very important. The government can pass laws and regulations that force the company to be compliant with certain environmental laws. Also, it can influence public opinion | Very committed to expanded production due to increased revenues (taxes, royalties, dividends) and increased employment for its population |

| #5 Indonesian Army and Police | Job security with expanded operations | Want to get more “lunch money” to keep peace in and around the mine | Important. Without the army and police, there would be chaos and theft | Committed to expanded production |

| #6 Environmental groups and NGOs | Negative impacts on the environment | Concerned with the effects of tailings on water quality, biology, and air quality | In the past, these have not been very important. Today, it is becoming more critical due to the negative reputation they created around this project. | Not committed to expanded production unless Freeport will implement a certain project to significantly decrease environmental damage |

| #7 Overseas Private Investment Corporation | Insured Freeport’s initial investment of $100M. No longer affected. | Canceled their policy in 1995 due to concerns about tailing management and disposal practices. | Not important at this point. | Not committed. Freeport also does not need them at this point. |

STAKEHOLDER INFLUENCE/INTEREST GRID FOR MINE EXPANSION

STAKEHOLDER COMMUNICATION STRATEGY

Manage Closely (Champions): #1. Shareholders, #4 Indonesia government

Keep Satisfied (Barriers): #3 Local indigenous Komoros and Amunge people, #6 Environmental groups and NGOs

Keep Informed (Advocates): #2 Current employees, #5 Indonesian Army, and Police

Monitor (Bystanders): #7 Overseas Private Investment Corporation

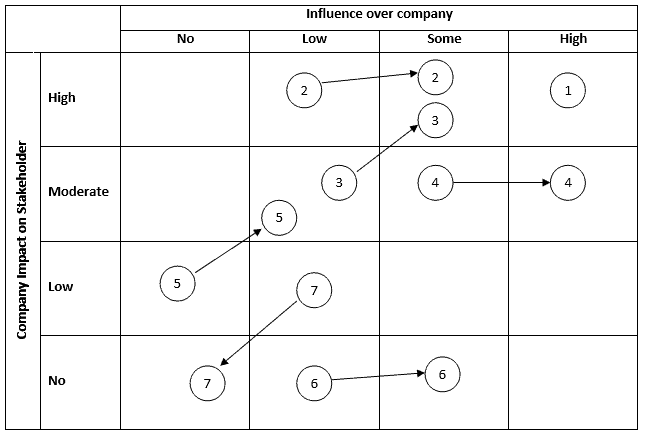

INFLUENCE GRID

Change over time (1945 – 2003)

MANAGERIAL STRATEGIES IN DISPUTES WITH NONMARKET STAKEHOLDERS

Source: https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1013&context=org_mgmt_pub

CHANGE PLANNING TOOL