This case study analysis focuses on the Greek crisis. It discusses the structural and political problems that led to the said crisis. It includes how other states and financial institutions participated to help Greece recover from the unfortunate event.

Dante Roscini; Jonathan Schlefer; Konstantinos Dimitriou

Harvard Business Review (711088-PDF-ENG)

April 05, 2011

Case questions answered:

- Was it unequivocally Greece’s fault?

- Was Greece assuming it would be bailed out?

Not the questions you were looking for? Submit your own questions & get answers.

The Greek Crisis: Tragedy or Opportunity? Case Answers

Executive summary – The Greek Crisis

The root of the Greek crisis was Greece’s structural and political issues that resulted in trade deficits, loss of revenue, and an increase in government expenditure and debt.

As the financial market lost trust in the Greek government, mostly due to Greek falsification of statistical data, Greece could not handle the crisis itself. Thus, two likely options for Greece were to default or get bailed out.

Greece eventually asked for the European Union and the IMF’s help since the Greek default would tremendously affect other countries’ economies in the area and the global economy.

The IMF’s leadership, Dominique Strauss-Kahn, wanted to help Greece gain political support for his presidential campaign in the 2012 election.

Analysis

1. Why was it unequivocally Greece’s fault?

The Greek financial crisis was a result of several problems within Greece. These problems can be divided into two aspects: structural and political.

a. Structural problems

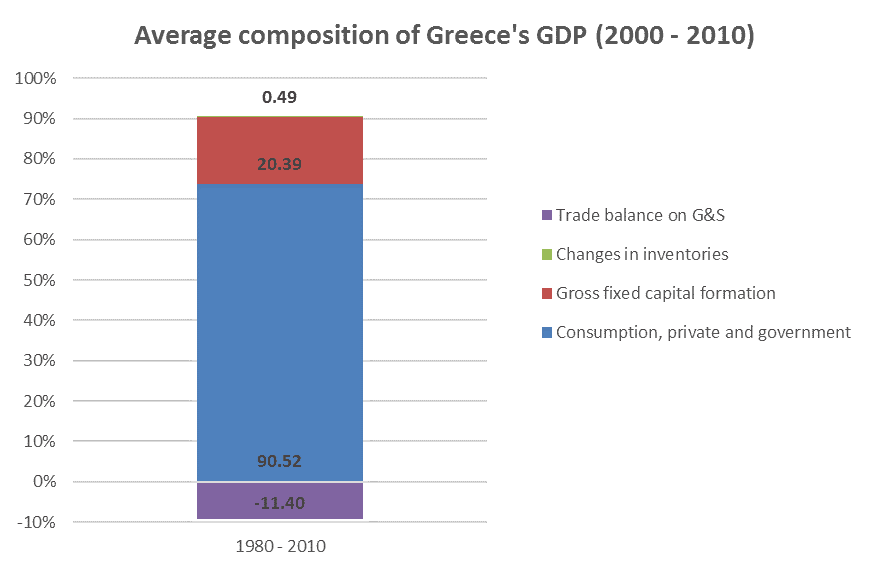

The first problem lies in Greece’s GDP composition. Exhibit 1 shows the average composition of GDP (%) from 2000 – 2010. Consumption accounted for roughly 90% of GDP during this period, whereas Gross fixed capital formation made up around 20%.

This means Greek growth was mainly from Consumption. Also, Greece’s agricultural and industrial outputs declined during this period, from 6.6% to 4% for agriculture and 21% to 16.9% for the industry. This helps explain the constant trade deficits, negative current accounts, and increasing government debt of Greece from 2000 – 2010.

Besides, Greece’s economy is based heavily on the service sector (roughly 80% of GDP in 2010). This sector largely consists of Tourism and Shipping, which easily suffered from economic changes such as recession and decline in global trade.

For example, during 2008 – 2009, the global financial crisis caused Greece’s services balance to drop 26% (from 17.1 to 12.6 billion EUR), and the result was the slowdown of the whole economy.

While Greece has potential comparative advantages in textiles, clothing, and refined petroleum products, low spending R&D might explain why industry only accounted for 16.9% of GDP and why Greece’s economy relied heavily on services.

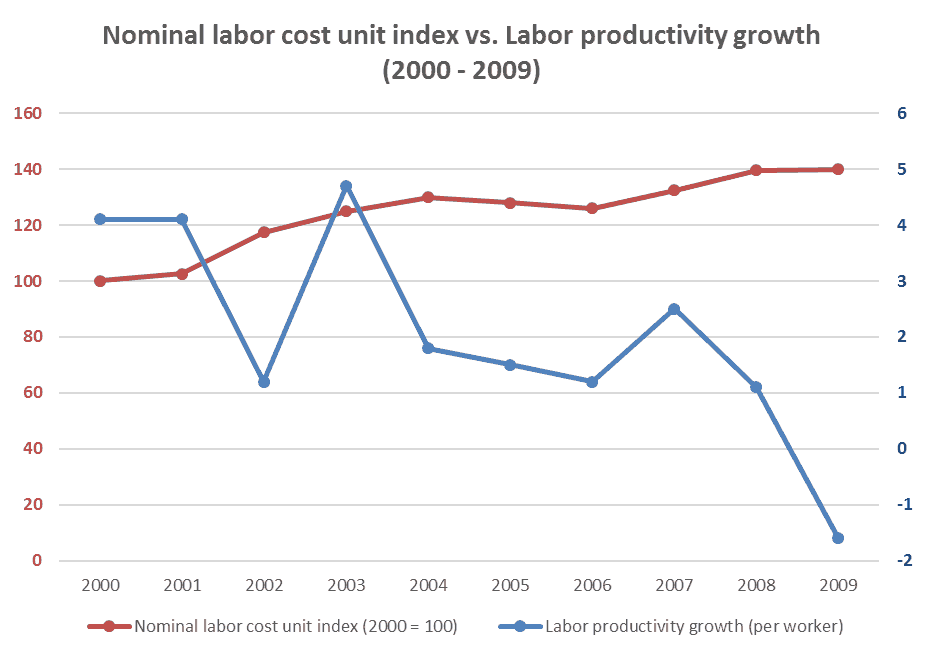

Greece also had another problem with productivity. While Greece’s labor productivity was among the lowest (18.2 EUR per hour (in 2007) only higher than Portugal’s 13.8 EUR per hour), it had the highest nominal cost index (124.5) as compared to other nations like Germany (99.3), France (114.3), and United Kingdom (119.7). From 2000 – 2010, although labor productivity growth slowed down (4.1 to -1.6), the nominal labor unit cost index increased significantly (100 to 140) (Exhibit 2).

This means Greece raised wages while there was no significant improvement in output per worker. As productivity is considered a major factor in economic growth, Greece’s productivity situation, together with the increasing debt and an inhospitable business climate, were clear signals of an inefficient economy and a financial crisis ahead.

b. Political problems

Greece also suffered from political problems that led to the crisis. These problems were caused by two governing parties: ND and PASOK. While both parties tried to win elections at all costs, Greece’s economy suffered.

For example, during the populist years, PASOK won the election by calling for social protection and income redistribution. This resulted in increased public spending from 29% to 48% of GDP, averaged deficits of 10% of GDP, and public debt tripled from 28% (1980) to 89% (1990).

Another example was the 2009 election. Efforts to win the election resulted in a relaxation of tax collection (revenue loss) and overstaffing issues (expenditure increase).

The relaxation of governing policies during election seasons probably created bad habits of following rules and policies for the Greeks. This negatively affected the Greek government’s revenue.

The Greek government could not collect taxes effectively since tax evasion and bribery have become the norm. Also, the Greek government could not impose tax laws on the informal economy (largely comprised of microenterprises and self-employed), thus resulting in losses on tax from 25% of the Greek economy.

Also, to gain more public votes, the Greek government significantly increased expenditure on the public sector.

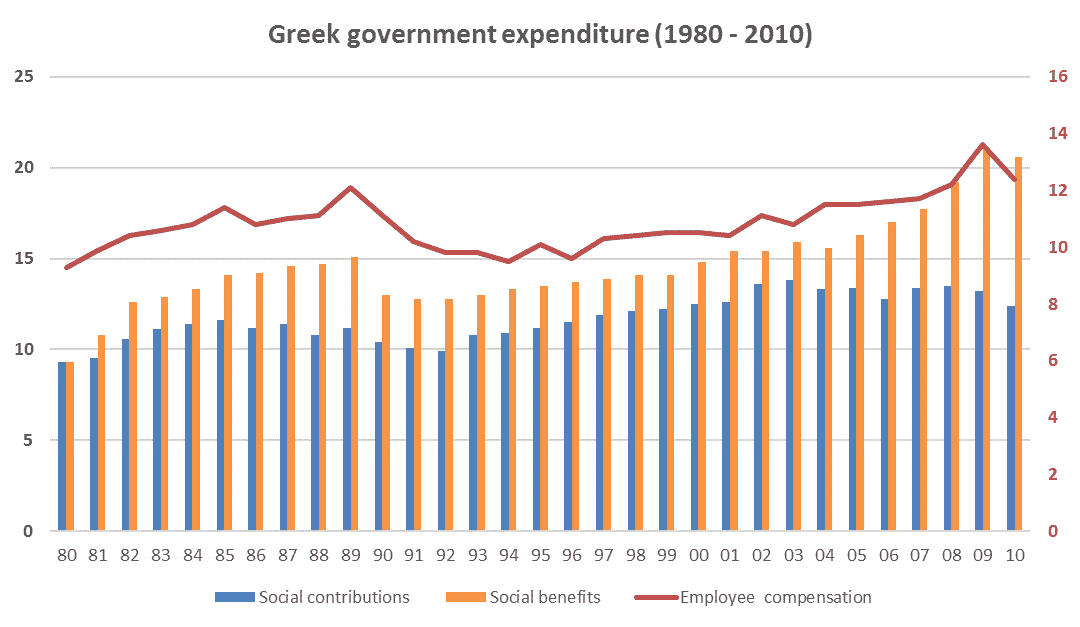

Exhibit 3 reveals trends in government expenditure on employee compensation and social benefits (compared to social contributions) from 1980 – 2010. There was a significant increase in compensation for Greek employees.

This resulted from the “complex, inequitable, inefficient and ripe for fraud” pension systems of the Greek government. Also, expenditure on social benefits exceeded revenues from social contributions, and the gaps significantly increased over the period.

Both employee compensation and social benefits peaked in the 2009 election year when the Greek government added 27,000 individuals to the public payroll to gain political support.

One major factor that contributed to the increasing debt of the Greek government was the low-interest rates resulting from the euro adoption. One can blame the euro for the financial crisis because it enabled the Greek government to take more debt at low costs to the point the Greek government could not handle the debts itself.

However, the ultimate fault was still on Greece since the Greek government should have used these low-cost debts to improve structural issues, such as investing in R&D to take the opportunity of potential comparative advantages in manufactured exports and balance trade deficits.

Greece had the lowest R&D expenditure compared to other nations in the area of spending on improving educational attainment. Greece was among the lowest to improve productivity, instead of excessively spending on employee compensation when it clearly did not increase productivity or provide any benefit to Greece other than political votes.

By looking into historical data of Greek government fiscal accounts and debt, it was clear that Greece was in an unhealthy economic condition, with a constant deficit from 1980 – 2010 and increasing government debt.

However, it was also clear that there was no solution or intervention from the European Union to improve Greece’s economic situation in time. This was probably because official data was disguised by the government, and thus, no countries in the European Union knew about the real situation of Greece.

By falsifying statistical data, the Greek government lost trust in the financial market, resulting in soaring interest rates and rating downgrades. Losing the trust of investors also made it impossible for Greece to resolve the problems itself since the financial market would remain skeptical about the Greek government’s ability to meet the payment deadline. Therefore, Greece should be most responsible for the financial crisis.

2. Why bailout was the only option

Since Greece did not control the euro, devaluation was impossible for Greece to resolve its problems. The most likely ways were to default or to get help from abroad (bailout). Greece might have assumed it would be bailed out by the European Union and the IMF for the following reasons:

a. European Union and the euro area

Greece’s default would create fears in the financial market that would put Portugal, Ireland, Spain, and Italy in the same situation as Greece since these countries shared the same traits of an unhealthy economy with Greece: high public debts and current account deficits. Therefore, these countries were likely to default next if Greece defaulted.

If these members of the European Union defaulted, the euro would suffer tremendously. Greece’s problems alone already caused the euro area exchange rate to drop significantly within 8 months (from $1.50 in October 2009 to $1.20 in June 2010).

The fall of the European Union’s members would make the area less attractive to other countries (Baltic nations). Thus, Europe’s plan to increase the use of the euro and turn it into a reverse currency would suffer. Also, since the Eurozone has a strong connection to the global economy, any negative effects on the Eurozone would affect the global economy eventually.

Not only these countries but France and Germany would suffer from Greece’s default as well since these countries’ banks were holding a large amount of Greek government bonds (60 to 120 billion EUR).

The Greek default would cause major problems to the banking system of the area and, thus, to the global economy. Hence, the European Union clearly had strong incentives to bail out Greece.

b. The IMF

Aside from attempts to mitigate the negative effects of Greek problems on the global economy, the IMF had another incentive from its leadership to help Greece.

Dominique Strauss-Kahn, then managing director of the IMF, was interested in bailing out Greece, considering that he was a possible contender for the French presidency in 2012, and two-thirds of the French public agreed to support Greece.

Therefore, generously helping Greece would also help Dominique Strauss-Kahn gain French public support in the 2012 election.

Appendix

Exhibit 1 – Average composition of Greece’s GDP (2000 – 2010)

Exhibit 2 – Labor cost unit index vs. Labor productivity growth (2000 – 2009)

Exhibit 3 – Greek government expenditure (% of GDP) (1980 – 2010)

(3 votes, average: 4.33 out of 5)

(3 votes, average: 4.33 out of 5)